Christ the King – A sermon preached at SS Peter and Paul, Weston-in-Gordano, North Somerset at Choral Evensong, 26th November 2017, 6pm.

Matthew 25:21-46; Ephesians 1:15-end

Today is the feast day of Christ the King, the very end point of the Church’s year. It is, as it were, the last word before the whole cycle begins again with Advent. And for our last word, we’ve got a humdinger of a parable to think about: that of the sheep and the goats.

I wonder how you hear this parable? How do you feel about the sheep who ‘done good’, and the goats who ‘done bad’? Is it comforting? Hopeful? Troubling?

I wonder what you make of the sentence passed on each of these: a pat on the back for the sheep, and a kick in the teeth for the goats.

I put it this way, because this is a passage of Scripture that lacks subtlety. You’re either a sheep or a goat. There is no cross-breeding here, no muddying of the species. It’s in/out, either/or, them/us. And if you’re anything like me, the niggling weed of worry that sprouts in the mind is this: am I a sheep, or am I a goat? Am I in or out, saved or unsaved, justified or condemned?

So I go to the Lord, and I make my complaint. “Lord,” I say, “life simply isn’t like this… you can’t just divide people into goodies and baddies and send the goodies off to be rewarded and the baddies off to be punished! We don’t play ‘Cowboys and Indians’ any more: we’re enlightened, 21st Century types! Don’t even the most virtuous have feet of clay? And who will we say deserves utter condemnation? And anyway, didn’t you say, Lord, that we ought to forgive our enemies – what was it, seventy times seven times? Will you not also forgive us?”

“What is going on, Lord? Do these words lack subtlety because you didn’t say them? Are they some kind of primitive ‘reward and revenge’ fantasy cooked up by the early church? Or does this parable’s polemic mean something? Is it meant to provoke something?”

“Come closer,” I sense the Lord whisper in reply. “Come closer and I will show you.”

As I’ve worried away at this passage this week, I’ve come to the view that its purpose is not to provide a literal description of the end of the space-time universe. Whatever we think the ‘Second Coming’ is, this bizarre scene is not simply “how it’s going to be”. In a week where religious violence claimed over 300 Egyptian souls in a single atrocity, I am not going to stand up here and preach divine vengeance, let alone divine violence. You’re not going to hear that sermon from me. The parable is certainly about judgement, but not in the way that we might think.

What we have here is apparently a picture of ‘the nations’ – all peoples, Jew and Gentile, Christian, and pagan. The division into metaphorical sheep and goats cuts across national and even religious lines. But did you notice in the passage, neither the sheep nor the goats have any idea which camp they are in? When Christ presents each group with its litany of merciful acts and unmerciful omissions, the nations are thoroughly bemused. “Lord,” say the sheep, puzzled, “when did we do these things”? “Lord,” say the goats too, “when did we not do these things?” They really have no idea how good or bad they are.

This gives us a clue to the meaning of the stark judgement we get here from Jesus’ mouth.

And the meaning, I think, is this: this passage wants to rid us of the illusion that we can accurately judge ourselves.

For example, after I’ve preached this sermon, if one of you makes a positive comment, I can almost guarantee you I will brim with pride on the inside – and then almost immediately try to squash that pride with false modesty. And if one of you makes a negative or indifferent comment, I will secretly blush with shame, and then instantly tell myself that really I’m actually pretty special, and who cares what you think. You see, left to our own devices, we will invariably judge ourselves either too harshly or too highly.

Imagine it like this: trying to see our true selves is like looking at a blip on a radar screen. On one side is self-righteousness and on the other is self-condemnation. The radar sweeps back and forth, with the occasional beep of truth, of self-insight. But it can’t rest there for more than a fleeting moment, because the radar is only sweeping our own perspective. We cannot know our true worth only with reference to ourselves. We will always get it wrong. We need something else.

In the last week we heard of the resignation of Robert Mugabe, a man who was once seen as a great liberator of his people, (a prime candidate for sheephood, perhaps). But Mugabe subsequently became seduced by power and hardened into a merciless dictator. Enter the goat. When Mugabe boasted that only God could remove him from office, it was a statement of supreme arrogance, but actually, in a way, he might have been onto something.

God is our judge. Whether it’s Mugabe’s tyranny, a jihadist’s zeal, or my angst-ridden middle-class guilt – we all stand or fall before God.

And so we find we need God-as-judge to save us from ourselves. We need God-as-judge because we can’t do it ourselves. We need God whose ‘wide-angle lens’ sees the whole of us, the height, weight, length, breadth and depth of us – and sees us as we truly are. Not the Sunday best version of ourselves. Not the Facebook version of ourselves. Not the sad, rather crumpled version of ourselves at our lowest points. Our true selves. A scary thought, but also, as perhaps we will see, the best thought.

Quite apart from any doctrinal wrangles about the Second Coming, quite apart from hoary questions about whether being a good person saves you from hell, I think this passage teaches simply that we are known by God, and judged by God – come what may.

But, if this passage is to be gospel, is to be ‘good news’, we cannot stop there. We cannot stop simply with the truth that God is our judge. For if we stop there, we will fall into the old problems and the radar will start sweeping again. We will either trapped by fear that God will not judge in our favour, or rest complacently in the belief that we are the chosen ones. Fear and complacency: both are paths to self-destruction, as you might recall from last week’s parable of the Talents.

The solution is that we need to raise our eyes from our own troubled breast, and lift them a little higher. If we want to know how God will judge us, then instead of asking ‘am I a sheep or goat’, we need to ask: “who is on the throne?”

Instead of worrying about being good enough, we need to ask: “who is on the throne?”

And the answer, the strange, earth-shattering answer is this:

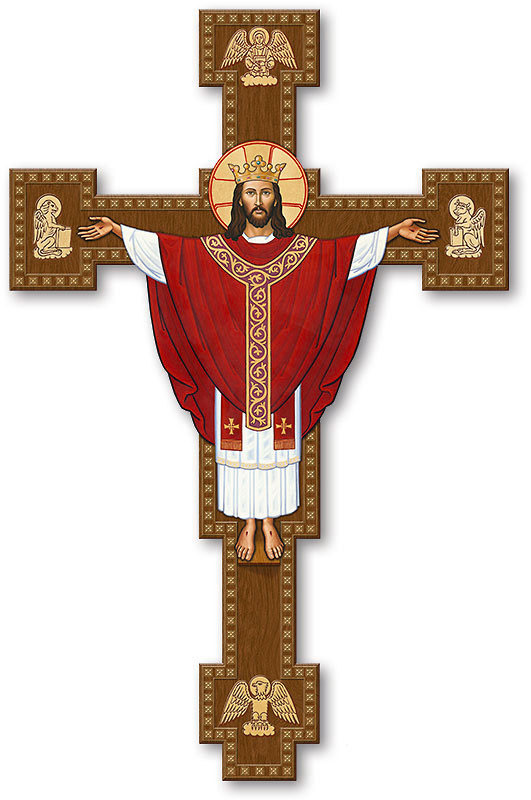

The One on the throne is the one on the Cross.

His judge’s seat is two planks of crude humiliation.

His crown is made of thorns.

His orb and sceptre are two nail-pierced hands.

His royal robes are purple bruises and scarlet scourges, humming on naked skin.

The One on the throne, is the one on the cross.

As we look to the future, I believe we have to look for God on the cross before we look for God in the clouds. It is when we look at the cross, that we see the lengths to which our God will go, in order to win all people to himself. When we fix our eyes on this God, all thought of self-justification melts away, for it is on the cross that we find, to our amazement, that our Judge has become our Advocate. The One passing sentence is the One pleading for us. And so what we call the “Last Judgement” is in fact, not the last word at all. The last word is love. Always love.

Sheep and goat, Christ died for us. Sheep and goat, God pleads for us. Sheep and goat, the eternal Spirit of God penetrates our pretence and sees us as we truly are – and loves us all the more. He will win us by love, or he will not win us at all.

We glimpse love in the cup of water we give to a stranger, the time spent with a sick friend. But even if we fail at these things – and we will, all of us – we nonetheless see love in its fullness, in all its humble majesty, in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus: love’s last word to us, to them, to all the nations of the world.

From thence to heaven’s bribeless hall

Where no corrupted voices brawl,

No conscience molten into gold,

Nor forg’d accusers bought and sold,

No cause deferr’d, nor vain-spent journey,

For there Christ is the king’s attorney,

Who pleads for all without degrees,

And he hath angels, but no fees.

When the grand twelve million jury

Of our sins with direful fury,

’Gainst our souls black verdicts give,

Christ pleads his death, and then we live.

(These closing lines come from Sir Walter Raleigh’s The Passionate Man’s Pilgrimage.)